One hundred twenty years ago, lawyer Paul J. Harris moved his practice to Chicago. While he enjoyed the new opportunity his adopted city afforded, Harris missed the friendly relationships he knew growing up in a small Vermont town.

One fall day in 1900, while walking around the Windy City’s North Side with Bob Frank, Harris noticed the connections his friend had made with local shopkeepers and it made him long for this kind of interaction. He wondered if, like himself, other professionals who had emigrated from rural America to the big cities, might be experiencing the same feeling of loss.

Over the next few years, Harris couldn’t stop asking himself this question: Could such human connection activity be channeled into organized settings for professionals and business people? Today we know the answer to Harris’ question is civic groups, but at the dawn of the 20th century, this innovation had yet to be invented.

Over the next few years, Harris couldn’t stop asking himself this question: Could such human connection activity be channeled into organized settings for professionals and business people? Today we know the answer to Harris’ question is civic groups, but at the dawn of the 20th century, this innovation had yet to be invented.

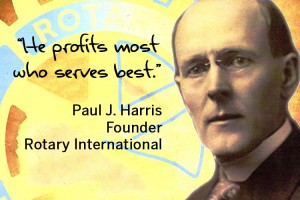

Then on February 23, 1905, Paul Harris put his connection question to the test when he and three friends founded the world’s first civic club. They named it Rotary because they planned to rotate weekly meetings between each member’s office.

Now an international success story, 33,000 Rotary clubs around the globe are still based on Harris’s founding principle of “Service above Self.” Harris’ original dream was to connect people for the benefit of all parties. He probably didn’t use this term, but his 1905 connecting formula is the modern definition of networking.

Three-quarters of a century later, Ivan Misner had a dream of creating a structured networking model when he founded Business Network International. Misner’s goal was very much like Harris’s but with the specific purpose of business people meeting regularly to help each other grow their businesses.

Though not a civic organization, the motto of BNI’s 7,400 chapters worldwide, “Givers gain,” is completely compatible with Rotary’s founding pledge. If you turned either one into an offer to someone else, you get what I call the Age of the Customer Power Question: “What can I do to help you?”

The significant international success of Rotary and BNI has revealed and reinforced two important truths: 1) networking is an essential professional discipline; and 2) putting others first is powerful.

This month Rotarians will celebrate the 111th anniversary of Paul Harris’ dream-come-true, and BNI celebrates International Networking Week. Whether you participate in a civic club, a BNI chapter, your local chamber of commerce or other group, become a more frequent, accomplished and selfless networker. Because face-to-face networking is the original social media and it’s still important.

Write this on a rock …In the Age of the Customer, you don’t have to join any group to ask and deliver on the Power Question.